The Orion Nebula — Messier 42 — in the Sword of Orion lies about 1,344 light years distant from Earth. Photo by James Guilford

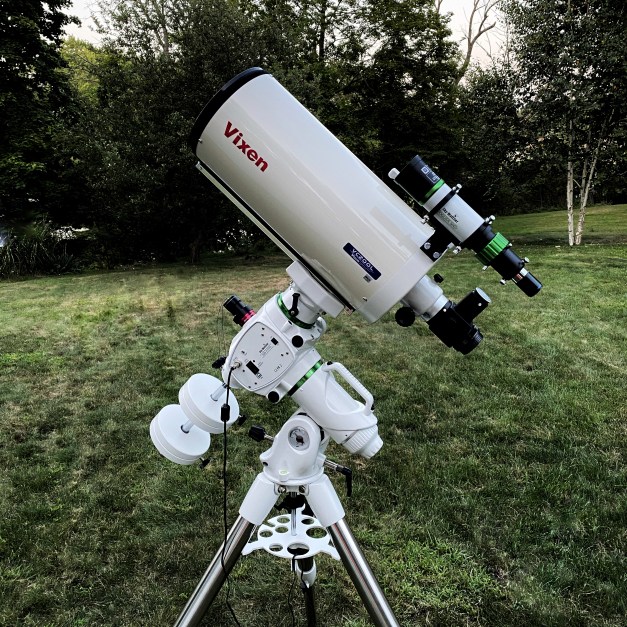

Taking advantage of a couple of strings of clear nights, I set up my telescope — now more usable than ever — and did a bit of imaging. I’m pleased to report that the telescope is more usable than ever thanks primarily to two things:

Mars during its opposition, or close approach to Earth, October 16, 2020. A tiny bright dot at the bottom is the planet’s polar ice cap.

I made some efforts at photographing Mars during its 2020 opposition — close approach — and managed “okay” pictures. That is to say, the resulting images were the best I’ve ever done but still short of what I’d like. I’m still working on technique and technologies and this may be the best I could manage given the relatively short 1,800mm focal length of my scope!

Star cluster Messier 2 — Messier 2 or M2 is a globular cluster in the constellation Aquarius. It was discovered by Jean-Dominique Maraldi in 1746, and is one of the largest known globular clusters. It contains about 150,000 stars and lies 55,000 light-years distant.

Around the same time I turned the telescope to try imaging bright star cluster Messier 2. There was a slight but noticeable improvement there over what I’d managed before.

In early November I set up the scope at night, using the polar alignment system, so that I would be ready for solar photography the next day. Of course I observed other objects that night but then I noticed Orion rising through the bare trees. I stayed up much later than I’d planned but when Orion’s Sword came into the clear I captured what turned out to be the very best images that I have ever made of the Orion Nebula! The brilliant Trapezium star cluster at the heart of the nebula got overexposed but I was thrilled how much of the area’s nebular cloud showed.

Full-disk image of our Sun with sunspot group AR3781 showing clearly. Sun is entering a more active phase of its cycle, for months there were few, if any, sunspots to observe.

A close-up view of sunspot AR2781, as recorded the afternoon of November 9, 2020.

I’m also very pleased with my efforts to image the Sun where a huge sunspot group (Active Region 2781) had appeared. The results were very good, using my telescope with Canon EOS 6D Mark 2 camera body attached for full-disk images. To protect camera (and eyesight) I used an AstroZap brand full-aperture white light film filter. Then I switched over to the little ASI178MC planetary camera; its smaller sensor providing a much-magnified effect. While not the best I’ve seen, I’m pretty pleased with this batch of solar images.

Telescope set up for solar imaging. The Canon EOS 6D Mk. 2 camera is in silhouette at the base of the scope while the little red ASI planetary camera rides above it. The blue box shades a laptop computer for use with the ASI.

So, even under our light-polluted skies, I’m able to manage some decent astrophotography. I’m sure that with time, practice, and clear winter skies I’ll get many more amazing views.

A Stormy Landscape. A large and dramatic shelf cloud approaches over rural Medina County, Ohio. Now possibly my favorite shelf cloud photograph, it’s an image made using my Apple iPhone.

After a long period without rain, Friday saw heavy rains and thunderstorms across the region. Most of it was a big wet mess, not well organized and not interesting to look at — at least not close to home. In the afternoon things changed.

I could see, via radar, that a promising area of activity was approaching but I had to move fast. The storm was approaching quickly and I had made my decision a little late in the game. I grabbed my phone, and one DSLR camera and rushed out the door.

Radar image shows the approaching strong storms. The blue circle indicates the photographer’s position.

Once cleared of city traffic, as I drove towards my target observation point I glanced to the south down crossroads. In the distance I could see a dark sky close to the horizon and … a light line running through the clouds parallel to the earth. It was big and it was close. A singular bright bolt of cloud-ground lightning held promise of exciting visuals, and not a little danger. I was also running late; I had to cut travel time.

A panoramic view of the approaching shelf cloud and storm over rural Medina County, Ohio. Made from several DSLR frames. Photo by James Guilford.

I changed destinations to a favorite site nearer home, pulled off the road, and unpacked the camera. I had arrived only just in time. Hurriedly shooting smart phone photos — a quick image insurance policy — I then shot a few via DSLR: a huge and beautiful shelf cloud was moving in from the southwest.

Fortunately, the lightning activity came to an end* and except for a quickening breeze and crickets in the grass, passage of the shelf was quiet. Only a few more shots and rain drops began. The tell-tale sight of approaching white sheets of rain sent me back to shelter in the car, and my photo shoot was over.

The results of my minutes-long efforts were surprising. The iPhone produced one of the best shelf cloud landscapes I’ve ever made; and a seconds-long video, also shot on the phone, drew use requests from cable stations: The Weather Channel, and WeatherNation. A big surprise!

*Safer without it but a lightning bolt during the video or, miraculously in the still image, would have been spectacular.

When we have a few expected clear nights strung together, I try and get out with telescope and/or camera to enjoy the night sky — such as it is in modern towns. And so it was that Thursday I set up the “new” Sky-Watcher mount with the intention of practicing polar and stellar alignment.

In order for a computerized equatorial telescope to aim at the celestial targets one seeks, it must be sitting level, it needs to know: where it is (latitude and longitude), what time it is — down to the second, the location of a couple of bright stars, and have its axis of rotation perfectly aligned with Polaris — the North Star — actually a specific point in space near Polaris! If you get all of those right, computerized mounts are great; you simply tap into a control device what you want to view, tap another button to tell it to “go-to” the target, and bibbidi-bobbidi-boo, motors whir, the telescope moves, and in a few moments you’re enjoying wonders of the universe. If you get everything right. If you don’t get everything right, it’s frustration and mosquitoes in the dark.

Waiting for Dark. The telescope sits atop its very demanding computerized mount, and sports a new finder telescope.

So Thursday night I managed to get the polar alignment better, probably, than I have ever before. I was using a telescope control app that seemed to occasionally get the location wrong and that’s a big deal. Eventually I was able to get the telescope to approximately locate objects and got decent views of Jupiter and Saturn before calling it quits — there was a lot of struggle involved. I put the weather cover over the scope and headed in.

Friday night was cloudy. I needed the rest anyway.

Saturday night saw hazy skies, glowing from ground-based light pollution but with cloudy nights ahead, I uncovered the telescope — already polar-aligned — and was particularly meticulous about date and time entry using the hand controller instead of the phone app. After a bit of trouble finding alignment stars in the soupy sky, I enjoyed seeing the message saying setup “COMPLETED.”

From then on, the system worked “as advertised.” So I keyed in Jupiter, and Saturn, followed by a number of other objects. Photography wasn’t the primary objective — conquering proper setup was — but with the telescope balanced for use with a camera, what the heck! I was glad I had the camera at the ready because many of the objects I wanted to view were not visible by eye in the milky sky. Time after time the scope pointed at the objects of interest. Wonderful! It’s been years since I had a go-to telescope work as well as this.

The field of view allowed the Perseus Double Cluster to be recorded in one camera frame. I was using my Canon EOS 6D Mark 2 DSLR mounted at the telescope’s prime focus — it’s essentially using the telescope as an 1,800mm telephoto lens.

One of my favorites, Messier 82, showed faintly in an image (also not shown here) and was invisible to the eye on account of light pollution. The pairing of M81 and M82 is one of my favorite galactic sights though a telescope; I’m going to need better skies or a different location to see them again!

My photos, though certainly not spectacular, revealed more galaxies than I’d yet seen in my lifetime. Barnard’s Galaxy (not pictured here) was revealed by the camera. I shot a photo of the star Mirfak because I thought it would be pretty with diffraction spikes. When I viewed the image on my computer, several small streaks with central bulges showed up — distant galaxies in the background!

Star Mirfak sports diffraction spikes making it seem to shine brighter. The spikes are caused by support vanes within the telescope affecting the light pattern focusing in the camera.

A first viewing and new fascination of mine is the Saturn Nebula: a planetary nebula around 5,200 light-years distant, which resembles planet Saturn in shape only. It’s a beautifully complex cloud of star-stuff that photographs in vivid color. Its image via DSLR is disappointingly small and required much cropping to see in any detail. I was delighted to capture a bit of its complexity and I’ll be visiting the object repeatedly for viewing and photographic challenge.

The Saturn Nebula. Clouds of stellar material glow, the aftermath of the death of a star. The oval shape of this planetary nebula resemble an unfocused image of real planet Saturn.

I also captured my best image, to date, of globular cluster Messier 2 — a beautiful ball of stars 55,000 light-years away. Capturing the brightest stars is easy but the cluster, one of the larger globular clusters known, is composed of around 150,000 stars. The cluster looks like a pretty fuzz ball by eye, photographs reveal some of those thousands of stars, and the best images look like diamond dust.

Flashes were lighting the sky to the south and east and clouds were beginning to flow in. A distant thunderstorm was drifting in my general direction. I called it a night at about 12:30 a.m., and tore down the entire setup stowing it in case of stormy weather.

It was a very good night, this further adventure in astronomy, giving me hope I’ve finally worked out the kinks and can more fully enjoy the experience.

Messier 101 — The Pinwheel Galaxy — in Ursa Major. The spiral and star clouds just emerging from the background. DSLR camera at prime focus of 1,800mm FL Cassegrain telescope. A first attempt that shows great promise.

All right, I know this is a weak and maybe ugly image of a beautiful gem of the night sky but to me it represents great promise. This was a target-of-opportunity imaging attempt I made after shooting comet photos. I keyed in M101 (for object no. 101 in the famous Messier Catalog) on the telescope’s control pad and with loud whirring the telescope swung up and to the north. Peering through the eyepiece at stars in a light-polluted sky, I manually moved the telescope … was that a little cloud in space, or a floater in my eye? Back again, yeah! That’s what a galaxy looks like through a small telescope: a little, dimly-glowing cloud. I shot a test image and sure enough, there’s something there. I shot a series of images, a series of “darks” — covering the telescope and recording the electronic noise of the camera’s image sensor — and called it quits for the night. So, after processing I got what you see above. I know I need to boost the camera’s ISO (sensitivity) and maybe the exposure time for each image. The image shown here is, however, the best photo I’ve ever made of an object outside of the Milky Way — the spiral arms show, star clouds and all. I know now I can do this and I hope the next attempt will actually be beautiful for others to see!

The Pinwheel Galaxy is a face-on spiral galaxy 21 million light-years away from Earth in the constellation Ursa Major. It was discovered by Pierre Méchain on March 27, 1781. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pinwheel_Galaxy

Comet C/2020 F3 (NEOWISE) glows green in close-up imagery. DSLR camera at prime focus of 1,800mm FL Cassegrain telescope.

Friday night, July 24, 2020, offered possibly the last best chance for me to see and photograph Comet C/2020 F3 (NEOWISE). The comet was nearing its closest approach to Earth but was speeding away from our Sun as it headed toward the outer Solar System — it was closer to us but dimming!

I met up with other astro-folk and photographers at a Medina County park. This time, having made photos capturing the scenic beauty of the comet in the night sky, I traveled with telescope and computerized mount. I wanted to see what “close-up” detail I might capture in the comet’s nucleus and tail.

The old Meade-branded mount fired up and, to my surprise, I quickly achieved good alignment using a compass and “eyeballing”. The recently-discovered comet wasn’t in the computer-controller’s database so I selected a spot as near the comet as I could and manually moved the telescope for aim. Through binoculars I was readily able to spy the comet, though it was noticeably dimmer than a week earlier. A companion and I both were sure we caught a naked-eye glimpse of the object through averted vision. It certainly did not reflect in the park’s lake waters.

So I shot a number of image series, experimented with various ISO settings, and shot a few images in “portrait” orientation in case I might record long cometary tails. That’s not what I got.

The camera recorded/rendered C/2020 F3 with a vivid green nucleus with a diffuse, reddish tail. Through the telescope I could see the greenish tint so I knew that was real and to be expected in the images. These close-up images are not what I expected but, I think, not bad; they serve as a farewell to a comet that brought a good deal of excitement to the amateur astronomical community in general and to me in particular.

Comet madness continued Friday night, July 17, as the region was finally blessed with clear skies. I ventured to a county park which extends after-hours access to my astronomy club, set up my gear, and waited for darkness and the emergence of Comet C/2020 F3 (NEOWISE). Twilight seemed to take forever to fade but finally I spotted the comet, and at a decent elevation above the horizon.

I shot many images, experimenting with stacking, using my 400mm telephoto, etc. but the shot I was hoping for and that I finally got was the comet above a glowing horizon, reflecting in the still waters of the park’s lake. Attempts at depicting the expansive and complex tails of the comet gave largely unsatisfying results; in part because our clear night sky wasn’t quite clear, or dark, enough to allow best imaging of the delicate details.

A portion of the Milky Way, above constellation Sagittarius. The bright “star” to the left is planet Jupiter.

When the comet finally faded in the west, I made a number of shots of the beautiful night sky itself. We rarely see the Milky Way these days. I grew up in a small town and, at that time, I could step out into the back yard, look up, and see the beautiful star trails of our home galaxy. It was a pleasure to see the Milky Way and get a half-way decent photo of it. I’ve included a labeled copy of the image below, in case you’re interested.

Purity and Pollution. Comet C/2020 F3 (NEOWISE) floats serenely above clouds illuminated by ground-level light pollution.

Comet C/2020 F3 (NEOWISE) was, for us in North America, a predawn object requiring exceptional dedication for observing. See a previous post. In the second week of July, the comet had moved enough in its orbit to become visible in the evening sky — from late twilight to about 11 p.m. Unfortunately, cloudy nights have been the rule lately so opportunities have been few.

On Wednesday night, July 15, the sky forecast was a bit shaky but it turned out the sky cleared enough to allow C/2020 F3 to be seen. I raced off to an observing site some 25 minutes away from home, popular with sunset watchers and, occasionally, comet spotters. Arriving at the site I found the place mobbed, the parking lot nearly full, by scores of would-be comet viewers. Unfortunately, the comet was pretty much at the low end of naked-eye visibility. Light pollution reduced contrast between comet and background sky to make the object nearly invisible. It’s likely most of those in attendance never saw the comet.

Binoculars quickly revealed “NEOWISE,” and a reference exposure I made of the area I expected to find the comet showed I was on target. I shot a number of photos but had problems with focus using the 400mm telephoto; I’m not happy with my “closeups.” As with my predawn photo experience, I found a wider view was much more interesting anyway and that’s what I’ve posted here.

Entitled “Purity and Pollution,” this picture (a single exposure of 8 seconds) shows a pristine wonder of the night sky floating serenely amongst the stars, clouds glowing brightly below illuminated by artificial light pollution. If we were only more careful with our artificial light, we’d save gobs of energy and gain back our starry skies as a bonus!

C/2020 F3 (NEOWISE) will be gracing our skies for the next week or so and I hope to have more than one opportunity to record the event before it is gone. The next apparition of this comet is expected in about 6,800 years.

Planet Jupiter and three of the four Galilean Moons are shown here, as imaged in the early morning hours of July 5, 2020. First Light for a new astronomical camera. And early efforts on new approaches to astrophotography for me.

I purchased a modest dedicated astronomical camera (ZWO-ASI178MC) recently, mostly for eventual autoguiding of my telescope during long-exposure imaging. The ZWO is described as a “planetary camera” so I thought why not? With Jupiter and Saturn near opposition and in good viewing position, let’s get first light tests using those beauties?

The penumbral eclipse of July 4- 5, 2020 was barely noticeable, even via telescope. The Full Moon, however, was impressive. Photo by James Guilford.

July 4 – 5 was the night of the very weak penumbral lunar eclipse and everything was set up in my yard for that. I had also made significant progress getting the new computerized telescope mount functional. Using SkyWatcher’s Wi-Fi module and my iPhone, helped immensely, providing precise GPS location and time information to the mount. Finder scope alignment helped, too!

So after finishing with the Full Moon and removing the DSLR camera from the telescope, I installed the little ZWO.

Planet Saturn shown here, as imaged in the early morning hours of July 5, 2020. First Light for a new astronomical camera. And early efforts on new approaches to astrophotography for me.

The camera worked well and I was quickly able to record images of Jupiter and Saturn. As a bonus, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot happened to be on the Earth-facing side of the planet. As for Saturn, I could see the image swimming on the computer screen so I didn’t expect much and didn’t get much. You can tell it’s Saturn and even begin to see some atmospheric banding.

Backyard telescope setup for the July 2020 penumbral lunar eclipse and later planetary imaging. This is an iPhone photo shot by the light of the Full Moon.

I still have much to learn about operating the camera control software and post-processing. As crude as the resulting images are, for first efforts the results are encouraging.

The night of July 5, 2020 brought Earth’s Moon, and planets Jupiter and Saturn together in the night sky in what is known as a conjunction. The bodies

Conjunction of Moon, Jupiter, and Saturn the night of July 5, 2020. Jupiter is the bright “star” above the Moon and just below the clouds, Saturn is the tiny dot next to the cloud to the far left of the Moon. Photo by James Guilford.

didn’t appear all that close together, but because Jupiter is at opposition — its nearest orbital position to Earth — it was particularly bright. Much dimmer Saturn was off at an angle from the Moon forming a sort of triangle, if one drew lines between them. Humans love to connect the dots. At any rate, I went out to the countryside to photograph the gathering, first to a favorite storm viewing site. I shot an assortment of images, watching the motion of a few clouds around the Moon and planets. The clouds, I thought, added to the scene. From my first stop, I headed farther west hoping to capture an imagined scene with Moon and planets reflected in the waters of a small lake. By the time I arrived at the second stop, what I thought would be my prime location, slow-moving clouds had rolled. I stayed on location for quite some time, listening to bullfrogs and shooing mosquitoes, while watching the clouds. After some time I called it quits, packed up the gear, and headed home. I am, however, very pleased with the “consolation prize” seen above.